With the words “We are going to try a Yankee Doge today, gentlemen, for making men insensible”, Robert Liston, senior surgeon at University College Hospital in London prepared to perform the first public operations in Europe involving the amputation of a limb while the patient was anaesthetised with Ether.

“The Yankee Dodge” to which Liston was referring to had been practised two months earlier on 16th October 1846, at a Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The hospitals first surgeon and principal founder, Dr John Collins Warren. He had successfully removed a tumour from the jaw of a 20 year old printer named Gilbert Abbot.

Ether was administered to the patient by a local dentist, Dr William Thomas Green Morton, who only a month earlier had become the first dentist to remove a tooth painlessly from a patient anaesthetised with ether.

Once Abbot was unconscious, Dr Warren cut away the tumour and shortly afterwards Abbot safely came around. ‘Did you feel any pain?’Morton asked him. ‘No,Sir,’ replied the young man ‘only some blunt thing scratching my cheek!’

Previously, operating without anaesthetics, surgeons severed arms and legs at high speed, while the patient, usually blindfolded and tied to a stretcher, remained fully conscious and screaming with pain, despite the piece of leather given to bite on.

The more compassionate surgeons mesmerised or hypnotised their patients, half suffocated them, made them intoxicated, sedated them with opium or froze the part of the body which was to be operated on.

Before serving as the anaesthetist at Warren’s history making operation, Dr Morton had been the partner of another Boston based dentist, Horace Wells, who was the first person to use nitrous oxide, or laughing gas as an anaesthetic in dental surgery.

In 1844 Dr Wells had one of his own teeth extracted while under the influence of nitrous oxide, and he later used it successfully on several patients.

Morton, however preferred ether as a means of killing pain. After his successful demonstration of surgical anaesthetic in a hospital, Morton patented his discovery under the name of ‘Letheon’.

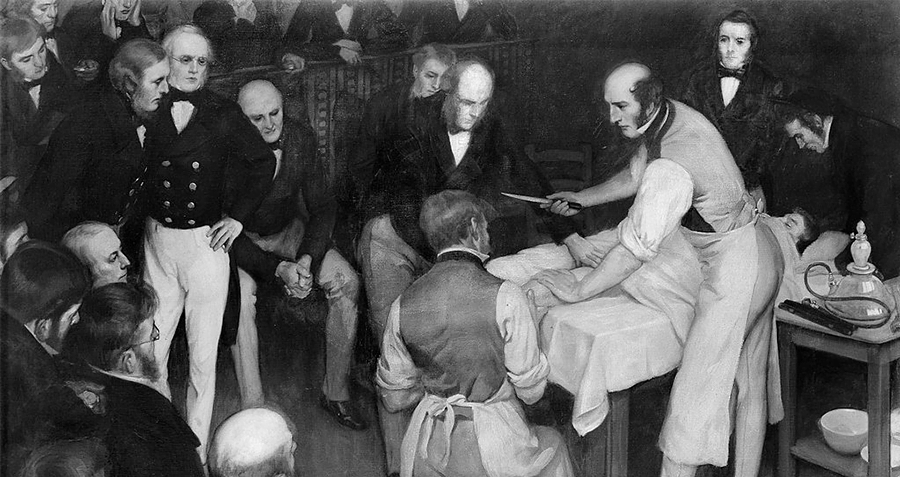

Meanwhile, Wells campaigned to have his own use of nitrous oxide, which he claimed was safer than ether, recognised as a surgical ‘first’. It was against this background that on 21st December 1846, the Scottish born Robert Liston prepared to follow Dr Warren’s example and operate on an anaesthetised patient.

Liston entered the hospital’s operating theatre wearing his customary coat and apron which were encrusted with months of accumulated dirt. A few moments later the patient, a butler named Frederick Churchill, was bought in. He had a diseased thigh that needed amputating.

A colleague of Liston’s then applied the anaesthetic by means of an inhaling device containing a sponge soaked in ether. Liston took a long, serrated knife and rapidly sawed into the thigh. He completed the amputation in some 30 seconds without Churchill feeling a thing. Liston then turned to a spellbound audience and said ‘This Yankee Dodge, gentlemen, beats mesmerism hollow!’

Among the onlookers that days was Joseph Lister, a 19 year old student who attended several of Liston’s anatomy lectures at University College.

Lister was appalled by the unhygienic conditions in the operating theatres of the day, which he felt must put patients at risk of infection.

At the time, the death rate in British hospitals following successful amputations was one in every three patients. In nearly every case the patients who died, did so a short while after their operations as the result of infected wounds, generally known as ‘Hospital Gangrene’.

Most doctors held that infection in operation wounds was caused by the entrance of air. Lister however, believed that germs in the air, not air itself, were responsible for the deaths in the overcrowded, unclean wards. Twenty years went by before Lister put his theory to the test.

In 1861, he was appointed surgeon to the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. Over the next five years he noted that some 50 per cent of the patients in the male accident ward died from sepsis, or blood poisoning, caused by infected wounds.

Then in 1865 Lister came across the work of the French chemist Louis Pasteur, who argued that disease was spread by airborne microbes, or germs.

Lister began to experiment with antiseptics, which he hoped would act to form a barrier between the wounds and the germs. After trying several chemical agents, he settled on carbolic acid, which until that time had been used mainly for cleaning foul smelling sewers.

Lister decided to try out the acid on patients with compound fractures, in which the broken bone had pierced the skin, often bringing about death through infection.

His first such patients was an 11 year old boy named James Greenlees, who was admitted to the infirmary on 12th August 1865. James’ left leg had been fractured and Lister dressed the wound with carbolic acid. The leg was then splinted and bandaged, four days afterwards the dressing was duly removed. There was no sign or smell of suppuration.

Over the next few days two more antiseptic dressing were applied and the wound began to heal. Just over six weeks after his accident, James Greenlees walked out of the hospital with his leg healed.

Feature Image of Robert Liston performing an amputation in front of a crowd of spectators. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.