After ten years of murderous toil that exacted a death toll of thousands of labourers, the Great Wall lay across the northern boundary of China like an enormous serpent.

Coiled along the land’s natural contours, it stretched westward from the Yellow Sea over mountains, through deserts and across farmland to the edge of Tibet.

The wall was built by the command of the first emperor of a united China. Shi Huand Di, whose state of Qin had overcome the other Chinese states and united them under his rule.

In 214 BC the emperor sent his general, Men T’ien to the empire’s northern frontier with an army of 300,000 workmen and an uncounted number of political prisoners to start building a chain of fortifications.

Hundreds of miles of fortifications had been built by China’s independent states. The task of Meng T’ien and his engineers was to strengthen or rebuild these structures and construct a further 500 miles (80okm) of wall to link them.

Work progressed at remorseless speed, new teams of labourers were constantly being thrown into the frenzy of the building work.

The human cost of building the wall was enormous and the peasants had to pay.

From every family of five at least two were dragged off to work on the wall, or similar grandiose state projects – a drain on manpower that made it almost impossible for families to run their farms.

Convicts sentenced to hard labour on the wall were marched hundreds of miles northward in chains and iron collars, they would drop with fatigue before reaching the wall.

Many of the conscripts died on the march. Those who survived the journey were housed in inadequate camps and put to work in blazing sun, driving rain, stinging hailstorms and temperatures that swung from 35 degrees at the height of summer to -21 degrees in winter.

Food was desperately short. The barren land could not grow sufficient crops and supplies had to be carried from huge distances by convoys of pack animals or manhandled in barges up swiftly flowing rivers. Much of the food was stolen by bandits, lost or eaten during the journey. Starvation accelerated an already high death rate and led to outbreaks of violence between workers and overseers.

Many of those who died of exhaustion or malnutrition were thrown into trenches dug out for foundation or buried inside the wall to act as guardian spirits against demons of the north, who it was believed were angered by the building of the enormous fortification.

The construction gangs started in the north-east and moved westward. First to be built were the watchtowers, most of them 40 f high on a 40ft sq base. Never farther apart than the length of two arrow shots, so that no part of the wall would be out of range of the archers. They were placed at strategic points along the wall such as hilltops or valley entrances. Between the towers ran a 20 ft high rampart to keep out potential invaders and demons.

Where the rock was available, workers laid a foundation or granite blocks – some of them as large as 14ft (4.3m) by 4 ft (1.2m). On top of this was built an outer frame of clay bricks or stone.

The mortar used for this in some sections of the wall was said to be so hard it was impossible to drive a nail into it, the formula for making it has long been lost. The central cavity in the wall was filled with earth and rubble which was then pounded solid. Ox carts, handcarts and donkeys laden with baskets brought materials from the surrounding areas.

In every area, building of the wall posed different problems. At the eastern end near a town called Shan Hai Kuan, the wall had to extend into the sea for a short distance, so boats were loaded with huge rocks and sunk to provide a foundation.

The central section of the wall was to run through the fertile Ordos region, home of the hostile Hsiung-nu nomads, here the tribesmen had to be driven from the area before building could begin.

In some regions, the hills over which the wall had to run were so steep that ox-carts and handcarts could no longer be used to carry the stone. Instead men had to carry loads of some 110lb (50kg) on their backs or in baskets suspended from a pole. On narrow paths materials were passed along a human chain.

Rocks that were too heavy for a man to carry would be rolled on logs or manhandled with levers inch by inch up the steeps slopes. Some areas that later generations could not believe that men had carried the building materials, claimed that goats must have been used.

Large section of the wall were built in areas covered with fine, yellow loess soil which was a poor building material. Here builders mixed the soil with water and poured it into wooden frames. As soon as it started to dry it was rammed into a solid structure to form the wall, which was then faced with stone or brick if they were available.

Some areas the earth was simply cut away to leave a strip of loess as a rampart: these sections of the wall proved far less durable than those in the rocky north-eastern areas. In the sandy areas of the Gobi Desert the wall was built by alternating layers of sand and pebbles with layers of desert grass and tamarisk twigs.

Once completed and fully manned the wall proved a formidable bastion. Each of the thousands of towers along it could accommodate a small garrison, stocked when possible with enough provisions to withstand a four month siege.

The line between the Chinese empire and the lands of its nomadic neighbours to the north had been clearly drawn.

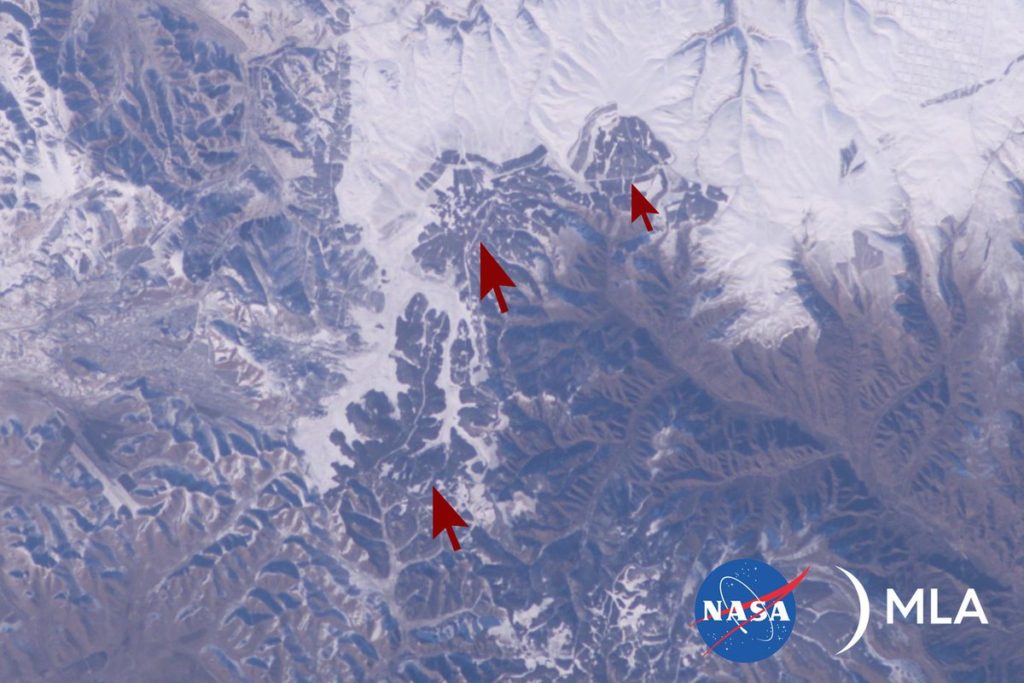

The great bastion is known to the Chinese as Wanli Changcheng, or 10,000 Li Long Wall and it stretches across northern China from the Yellow Sea to central Asia, extending for 1500 miles (2400 km) from west to east and totalling 4000 (6400km) with its many branches.

The wall is the largest structure built by human hands and is the only man made construction visible from space.